|

Unlike many of his predecessors, Hick

does not punctuate his assessment of the rigid exclusivity within the

many other faith traditions with condemnation or rebuke. Instead, he

argues that the theological error which he describes occurs naturally

as a function of the human condition. As he notes “Psychologically,

then, the sense of the unique sense of superiority of one's own

religious tradition may be simply a natural form of pride in an

engrained preference for ones own familiar group and ways.” For

this, Hick's argument has a strong element of persuasiveness. It does

not alienate, and therefore, does not provoke so much instinctive

criticism. He presents a refreshing sense of twentieth century

optimism, anticipating Star Trek and the fall of the Berlin Wall,

both of which played heavily on themes of unity, globalism, and

cooperation.

The problem, Hick says, is that

“natural pride...becomes harmful...when elevated to the level of

absolute truth.” In such cases, he argues, the results include

“persecution, coercion, and repression.” A less contentious

solution is a “reality-centered” conceptualization of faith in

which “another product will serve as an adequate second best.”

Tolerance, Hick understands, is extremely becoming of a religion of

peace. With a secular world drifting away from traditional values and

cultural patterns, the strenuous divisions of faith create a

contentious atmosphere of suspicion and resentment, especially as the

many groups vie for political influence and carve out there own

communities. This process likely does more to sustain secularization

than it does to attract new followers. In a sense, what Hick is

saying is that the religions of the world have a great deal of

incentive to set aside their minor cultural differences in favor of a

cooperative and mutually inclusive relationship.

By and large, research indicates that

the majority of the faithful in America are more likely to identify

more closely with Hick's message of religious equality, but the

fringe radical groups are several orders of magnitude more vocal, and

therefore, more likely to be heard. However, each group has

demonstrated a need to accommodate some particular shift in social

evolution in order to survive. In light of the gay riots in New York

and gay boycotts in San Francisco, hatemongers like Jerry Falwell and

Anita Bryant compromise the benevolent nature of Christian theology

to reign in the socially mal-adapted audiences that will consistently

vote on religious cues. On the other hand, however warm and inviting

Hick's utopian hypothesis might appear, it is also a deliberate and

necessary attempt to dial back the eighteen hundred years of failed

social principles against which Marx had once taken his humanist

stand. He leaves open the question of how to resolve natural conflict

between secular and religious authorities. He avoids the Christian

and Muslim mandates to convert, evangelize, and proselytize. He

dodges the then-half-century-old Arab-Israeli crisis, the conflict

between Sharia law and the Cataclysm, and escapes without

consideration the many atheists in the middle.

Effectively, because one may assume

that John Hick is not widely read in the non-Christian, non-academic

world, Hicks message of concilliarism mostly implies a fragile

reconciliation between the Lutheran and the Baptist who happen to

find themselves co-inhabiting a set of bus seats on occasion. Odds

are it will find little meaning or value in a world struggling to

decide how to deal with organizations like ISIS and the KKK.

Hick also quietly dodges a more

plausible explanation for the emerging trend toward religious

pluralism in spite of dogmatic supremacy. In recent years,

researchers have demonstrated pretty convincingly that atheists are

often more well versed in Christian doctrine than Christians

themselves. There is a fascinating engine driving this phenomenon.

Christianity itself is a complex matrix of debates, discoveries,

decisions, and demands which grew out of centuries of exploration,

tradition, inspiration, and reflection. The learning curve for new

Christians might as well be a perfect vertical line compared to that

of the early church fathers. Each particular denomination is

different from the next, and after a generation or two of dogmatic

drift, neglected exploration, and artistic license, no religion can

confidently hold its adherence to any very unique set of

expectations. In short, what people actually know about their

religion is in decline, as access to other, more interesting subject

matter competes for a progressively greater share of public

attention. Conversely, what there is to

know about religion in general increases exponentially as more and

more theologians examine and discover and publish. It makes sense

then, that at some point, these religions would tend to blend

together in a grand theocratic wash. Though Hick's approach is novel,

in a way, he is just following

the logical path of least resistance. The world is secularizing

because of science, not sin, and not because of anyone's concept of

religious supremacy.

There are few

easier subjects for contemplation than a world in which everyone gets

along. Or that the subject one has devoted one's life to isn't slowly

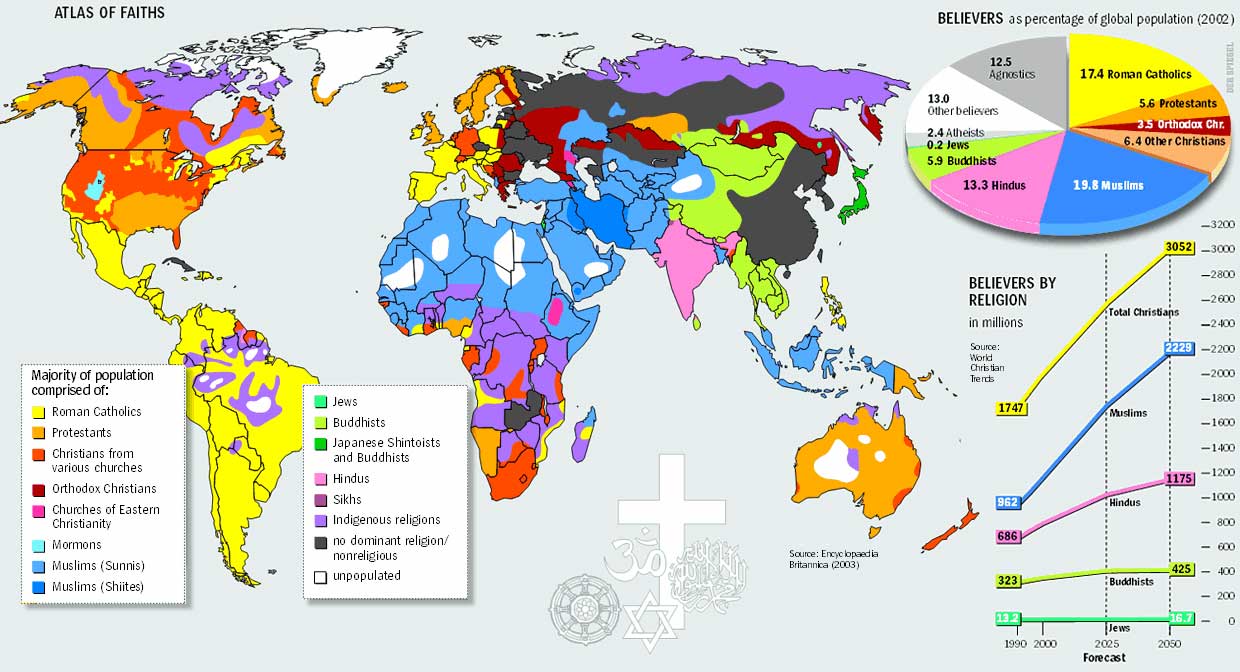

disintegrating beneath one's feet. Image Source: http://www.china-mike.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/map-world-religions-chart.jpg