Featured Post

December 11, 2014

Welcome to the Universe

December 10, 2014

The Arab Side of the Jewish Question

|

The best explanation for the persistent hostility between Arabs and Israelis, in painfully cynical terms, is the absence of a powerful Arab lobby in the history of the American political machine. The academic answer is far more complex, but it is this peculiar distinction that must be credited, not with the origin of the Arab/Israeli conflict, but certainly for the tragically resilient blood feud narrative into which the conflict grew, and the international conspiracy which not only sustains the crisis, but literally thrives upon it. The declaration of Israeli Independence on 14 May, 1948, condemned generations of Jews and Arabs to a life of violence and brutality. The powerful irony, however, is that the Zionist movement, upon which this new state was formed, began as an altruistic attempt to save a seemingly doomed race of mercilessly embattled European Jews from inhuman atrocities committed by and/or under the unconcerned eyes of their neighbors, police, soldiers and rulers, who mostly viewed the Jews as Christ-killers, and worth little more consideration than that.

Modernization and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire is famous for its size, scope, and influence upon the histories of nearly every major European country. Why then, did the concurrent attempts at modernization seem to fail for Turks, where the Egyptians succeeded? In short, the Turks, who wielded so much power and authority, failed to solidify their gains. One argument, and a strong one, is that they bit off more than they can chew. Another argument, equally compelling, is that they were simply beaten into bankruptcy. And yet another argument contends that reforms failed for Ottomans because of an insurmountable surge of internal resistance, from basically every direction.

December 08, 2014

The Contemporary Crucible: A Stage Review

Shreveport Little Theater and Heather Hooper teamed up to bring Arthur Miller's frustratingly resonant McCarthy Era masterpiece to life in a brilliant, on-stage production that only the deep south can truly deliver to form. Though at-times high-school-esque in cue and oration, local performers quickly descended from their traditionally contemporary sets and yoga-panted characters into an immersive frenzy of intrigue, confusion, and madness. Needing little artistic license to recreate the dialects and scenic commonalities of religious social influence, Hooper's cast takes conservative advantage of that stereotypical southern twang so often characterized as a bane to artistic and intellectual culture, and delivers a powerful (and disturbingly familiar) rendition of an age-old American theme: Persecution.

December 07, 2014

The Empire Fights Back

|

In the 19th century, the so-called “balance of power” which western nations sought after the atrocities of an unrestrained Napoleon finally began to shift, from Ottoman, to European favor. Having been stopped twice at the gates of Vienna centuries prior, the Islamic tide slowed to a trickle as the unification of Russia and Germany began to solidify resistance to Ottoman control. As the Ottomans struggled to respond to a rapidly changing set of enemies, Persians and Egyptians endured their own internal changes as well. Together, these three centuries-old Islamic players on the world-stage would suffer the intense stranglehold imposed by British, Russian, and French imperialism. The consequences would forever change the middle eastern perception of its own security forces, and would, in many cases, undermine internal diplomacy as sweeping attempts at reform drew the ire of tribal and religious conflict. The result for Egypt was a strong nationalist dynasty that would persist into the mid-twentieth century. For Persians in Iran, it was the beginning of a long history of proxy wars and shaky alliances forged more often out of necessity than opportunity. For the Turks, however, these Christian thrusts into the “Islamic Heartlands” posed an existential threat to the already-withering Ottoman Empire.

December 05, 2014

Saints, Martyrs, and Marxisms

Though Karl Marx's indictment of the Christian religion in Social Principles reflected the irreverent indignation of a seemingly oppressed dissident, both angry and tinged with callous cynicism, it is difficult to relegate his commentary to mockery. Marx writes with great passion about the unfavorable outcome of what he treats as kind of a grand, eighteen hundred year long experiment.

The great irony in the western religious and political rejection that walled off what became a semi-Marxist empire and a dominant global socioeconomic force is that beneath his rebellious tone, what Marx suggests about mainstream institutional religion only echos the cries of many so scholars, prophets, and reformers which precede him.

What links Marx with the most fervently radical religious fire-and-brimstone preacher, with the most prolific humanitarian saints, and with the most successful church reformers is the courage to hold what is arguably the world's most important governing authority to its own standard. From this vantage, Marx is greatly humanized by the retrospective concession that he himself was not completely to blame for the conclusions he drew from what he observed of history. To treat Marx fairly, therefore, is to grant the possibility that had the church evolved into a less contentious, more edifying presence in Marx's world, he might have embraced it for its many virtues. Instead, Marx lived in the long consistorial shadow of a much more invasive and authoritarian animal, whose ravishings were visibly inconsistent with the Christian message of peace, comfort, redemption, and faith.

In

any setting which finds bureaucracy governing matters of morality and

thought, as when there is no boundary between church and state, the

two become indistinguishable. The “double-wings” which provide

“in-exhaustible life” in Marx's metaphoric treatment of the

Prussian eagle, did so on the strength and sweat of a severely

disenfranchised population, and did so for the advancement of

hostile, alienating forces. If the premise of Christianity is that

God is in control, how else could a mind like Marx interpret the

world he saw? When he writes “One third of the nation has no land

for its subsistence...[with] another third in decline” his

complaint would fall silent on the ears of God and Holy

Roman Emperor alike. In his

view, the failure of the one through centuries implies, if not

guarantees, the failure of the temporal models of the other, which

predicate themselves upon theology.

When

Marx describes Prussian Consistorial Councilors as having “imaginary

blanks checks, drawn on God, the Father, and the Company,” it is

not difficult to see how he draws the line from “justification of

slavery in antiquity,” through the “[glorification] of medieval

serfdom” to the “defense of oppression of the proletariat” in

his own time. While for many historians, the past is a long and

intricate series of battles, intrigues, and expeditions, Marx took

the furthest step back and painted the last few thousand years with

the broad stroke of admonition, for both the takers who thrived on

the broken backs of the poor, and for the sublimated minds of the

chattel which whinnied

on, generation after generation, toting the cannibal dwarves on their

giant shoulders.

Marx

observes what, in his view, represents the greatest human tragedy

perpetuated by the cruelest of schizophrenic rationalizations: that

this servitude of dehumanizing guilt and blatant exploitation is

eternally imposed upon this race of men as either “just punishment

or suffering for the redeemed.” Marx is often treated by critics as

a proponent of violence, which is a distinction often used to mark

the disparity between the messages of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X

in the American rights movement era.

This characterization fails to objectively acknowledge the urgency and sincerity of Marx's perspective. His was not the world of idle philosophical musings in suburban comfort. That Prussian Eagle would ultimately become a casualty of ideological world war between well entrenched members of an inbred family of divine right rulers operating and expanding in tandem with their faith traditions. Soldiers were followed by missionaries or sects of dissident refugees, who, in turn, were followed by new governments, rapidly modernizing security forces, producing new soldiers, from which inevitably proceeded more refugees, dissidents, and always, new governments.

Everywhere in 19th century Europe, the erased identity was a common theme. Entire cultures were weighed against bullets and gravestones. And all the while, soft voices whispered, “relax, everything is under control, there is a plan, His plan.” What even Marx struggled to articulate was that ALL humans are bound by their own imperative, either to resist or be subdued. Slavery is a condition of the mind, and not of the shackle or whip. To turn the other cheek enough times, as Ghandi famously did, in Marx's view was to effectively teach the abuser that one condones the abuse.

While Absolutists

may defer to Gandhi's example, Marx addresses the much more typical

result, with which he equates the outcome of the whole Christian

experiment: a world in which humanity is defined by “cowardice,

self-contempt, abasement, and submission.” Where the faithful are

content to ask only for their daily bread, Marx places greater value

on “self-respect, pride, and a sense of independence.” With this

principle, even the staunchest of cold-war hawks and apocalyptic

evangelists might have found common ground in the age of

democratization and Manifest Destiny.This characterization fails to objectively acknowledge the urgency and sincerity of Marx's perspective. His was not the world of idle philosophical musings in suburban comfort. That Prussian Eagle would ultimately become a casualty of ideological world war between well entrenched members of an inbred family of divine right rulers operating and expanding in tandem with their faith traditions. Soldiers were followed by missionaries or sects of dissident refugees, who, in turn, were followed by new governments, rapidly modernizing security forces, producing new soldiers, from which inevitably proceeded more refugees, dissidents, and always, new governments.

Everywhere in 19th century Europe, the erased identity was a common theme. Entire cultures were weighed against bullets and gravestones. And all the while, soft voices whispered, “relax, everything is under control, there is a plan, His plan.” What even Marx struggled to articulate was that ALL humans are bound by their own imperative, either to resist or be subdued. Slavery is a condition of the mind, and not of the shackle or whip. To turn the other cheek enough times, as Ghandi famously did, in Marx's view was to effectively teach the abuser that one condones the abuse.

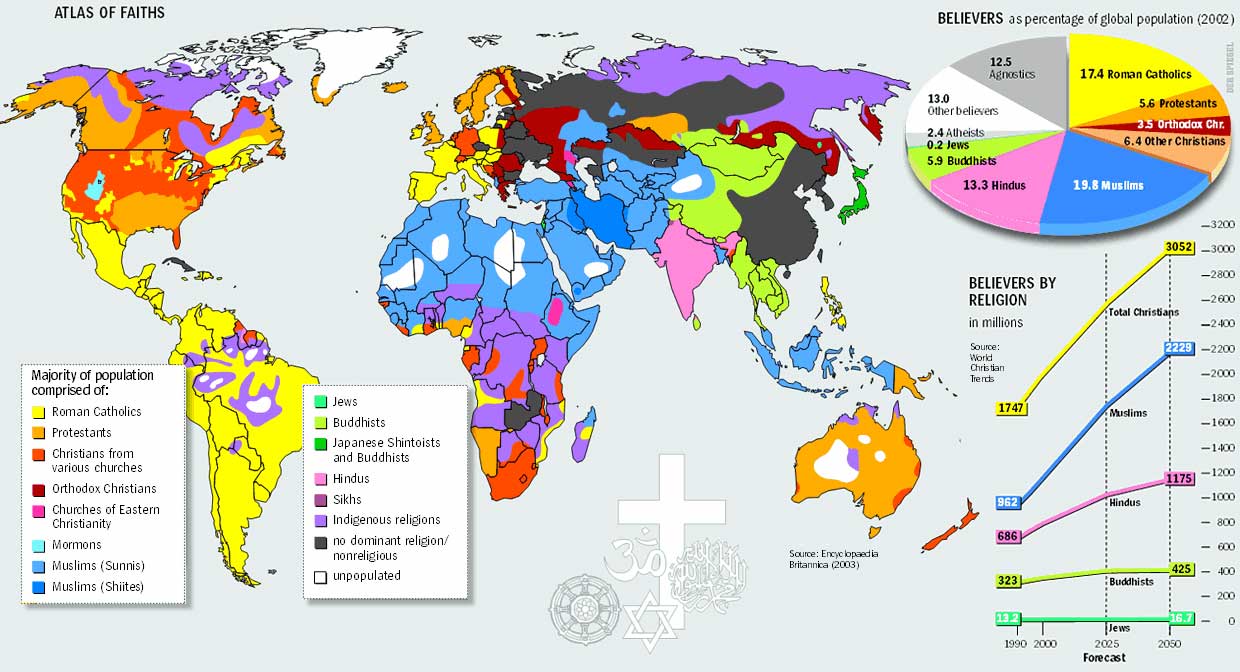

Image Source: http://img11.nnm.me/d/3/6/7/7/5110c242d3c0108cd60de7ad427.jpg

Stood Up by Jesus

To understand Ellen White's Great

Controversy concerning the

Sabbath, it is necessary to first discuss the Day-Age Theory which

inspired the Millerite movement, in which followers of William Miller

assembled a series of scriptural passages which they maintained, when

decoded, revealed what they believed would be the year of the

rapture. White elaborates extensively on a careful examination of

passages from Daniel, Ezra, and Mark with the assumption that the

references to day, or

days, should be

translated as years instead, as extrapolated from associative

references in Numbers and Ezekial, and set against a timeline of

known biblical events. Drawing on Miller's equation of the word

sanctuary with the

earth and the word cleanse

with the second coming of Christ, White demonstrates how the passage

from Daniel could be interpreted to support Miller's famous claim

that the world would end (or change profoundly) in 1844.

Falwell Rising

On Religious Pluralism

|

1001 Nights of Revelation

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)